Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, or EMDR, can appear to be a very unusual form of therapy when people are first introduced to it. The idea that eye movements can help process uncomfortable memories can seem very strange for those of us who believe the stereotype of therapy involving hours of talking through life experiences in great detail.

But just how much talking is involved in EMDR? Does it require as much conversation as standard talk therapy? People that are thinking of undertaking this process sometimes want to know exactly what they will be expected to talk about, and how much they’ll need to discuss it. The answer on this may surprise you.

EMDR therapy does involve a little bit of talking, but much less than conventional psychotherapy. The main aim of EMDR is to remain present with whatever experiences, thoughts and feelings come up. There is no requirement to talk about distressing events in detail if the client does not want to.

A reminder that not all therapists are qualified to administer EMDR. If you are looking for an expert we recommend trying Betterhelp where you will find several EMDR therapists at the fraction of the cost of offline EMDR sessions. You can start by filling out this form to be matched with a therapist.

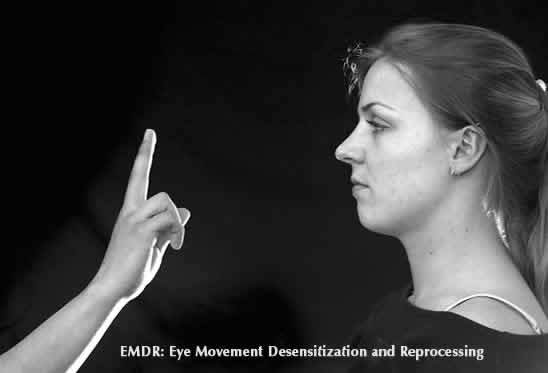

It is this process of remaining mindful of one’s internal experience, whilst also focusing on the outer stimulus of the therapist’s hand moving from left to right, that EMDR is thought to derive it’s power from in helping clients process difficult memories.

Talking about memories forms a much smaller part of the process than in other forms of therapy, and is not really central to the process as it would be with other types of therapy.

This can make EMDR a very useful form of therapy for those who remain burdened with unpleasant memories that they want relief from, but do not really want to discuss in great detail.

Let’s look in more detail at how the EMDR process work in relation to talking and conversation.

Contents

Some Talking is Involved in EMDR

The EMDR process does involve some talking, but it is quite limited, especially once the eye movements and processing are underway.

In fact, most of the talking happens at the start of the process and a little bit at the start of each session. Other than that, conversation tends to be minimal, certainly compared to standard talk therapy, which is nearly all conversation and verbalizing.

The very first session you have with an EMDR therapist may feel a bit like a standard session of talk therapy, as you and the therapist draw up a life history, or “timeline” of key events that you want to work on.

There may be some back and forth discussion about this, just to draw out key overarching themes and patterns. A skilled practitioner will not make you dicuss anything you don’t want to though.

Once this is out the way though, conversing will not be a big part of the process – the main focus is on reactivating key memories and using the eye movements to process them to resolution.

Here is a very quick overview of how EMDR works, in relation to talking:

- In the early stages of the process, you will draw up a client history, which may involve some talking as you go over key memories from your life and draw out key cornerstone or “standout” distressing experiences you can work with. You can remain general rather than specific about this if you want to.

- To begin the process, the therapist will ask you to “tap into” a certain memory, by remembering sights, sounds, smells associated with it. You can do this verbally or non verbally if you want.

- Once you feel “tapped in” to a memory, the therapist will ask you to stay with your internal experience and initiate the back and forward eye movements, using their hands, light bar or some other stimulus. There is usually no talking involved here; you are just moving your eyes back and forward while staying with your internal experience.

- This usually continues for about 20-30 seconds. After this, the therapist will ask you if anything else has come up (other memories, thoughts, feelings etc). You can choose to talk about what’s coming up or keep it private – the choice is yours.

- The therapist will ask you to stay with whatever else has come up for you, and then re-initiate the process of the back and forth eye movements.

- It is the dual focus of attention – staying present with your internal experience whilst also focusing on the outer stimulus – that is thought to allow the mind to “blur”, or process the memory, lessening it’s intensity without needing to talk a great deal about it.

- The therapist will continue to repeat this process as your mind keeps moving onto new memories and thoughts – notice internal experience, follow stimulus with eyes for about 30 seconds, notice what else is now coming up, stay with it, start eye movements again.

- Once this process gets going, there usually isn’t a great deal of talking. You can remain as general or specific as you like in talking about what comes up, or even say nothing if you like.

- The therapist may stop periodically to talk about what has come up a little more. Again, you don’t have to go into great detail if you don’t want to.

- The therapist may also ask you if any other memories have come up between sessions. Again you can go into specifics or remain very general if you like.

- See our full article on the 8 step EMDR process for a description of the EMDR methodology in much more detail.

Tapping Into a Memory with EMDR – Example

“Your job is simply to notice what comes up”

EMDR Does Not Involve as Much Talking as Normal Therapy

What we have covered so far indicates that EMDR does feature nearly as much talking as conventional therapy would. In standard therapy, most or all of the sessions involve talking and verbalizing. In EMDR, only a minority of the process involves talking about memories.

In addition, much of the talking that is done in EMDR is not done for the same reasons or with the same goals as in standard therapy.

In talk therapy, any conversation is usually done with the goal of exposing or resolving conflicts and contradictions, or gaining information to improve the therapist’s knowledge of the client’s situation, seeing how certain things may interconnect and identify certain patterns.

In EMDR, some of the early “life history” discussion may be done with this in mind, but once the process is underway, the main goal of verbalizing is simply to help the person “tap in” neurologically to unpleasant memories, getting as much as possible back into the emotional state they were in at the time.

It is this reactivating of the memory, sometimes (though not always) though talking a little bit about it, that allows the processing to work, with the eye movement “blurring” the intensity of the memory once it has been tapped into, lessening it’s effect on the person.

Therefore we can see that EMDR approaches the whole idea of therapy in a very different way to the conventional approach, seeking a more “core” level philosophy of simply accessing and dissolving the unprocessed emotions surrounding key life events, rather than talking about the life events in great detail, which may or may not provide relief based on the person and the life history.

See the table below for a good comparison of EMDR versus other forms of therapy.

| Type of Therapy | Views source of psychological disturbance as: | Treats With: |

|---|---|---|

| Psychodynamic Therapy | Conflicts in the conscious/subsconscious mind | Talking, verbally working through conflicts and contradictions |

| Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) | Dysfunctional beliefs and behaviours | Directly challenge and modify these beliefs; set homework tasks |

| EMDR | Unprocessed memories stored in the body/brain | Access and process these memories using eye movements and other stimulus |

During EMDR, the focus is on staying present with whatever comes up internally, not necessarily discussing it if you don’t want to

You Don’t Need to Verbalize Uncomfortable Memories in EMDR

This can be a big advantage of EMDR versus standard talk therapy. The latter can involve the painful dissection of distressing, embarassing events in conversation; the former need not.

In EMDR, the emphasis is not on verbally talking through past events in great detail. There is some talking required, but only a limited amount, and only to tap the person into negative feelings associated with events, and discuss any connecting memories which come up, if desired.

In other words, in EMDR the therapist is not asking you to talk about memories so they can get information they need to know; it is more to bring you back into a state where some of the feelings you felt at the time are reactivated, which can then be processed using the eye movements.

In the first few sessions, when the therapist is explaining the EMDR process to you, they should point out that if at any point, you do not want to talk about anything that comes up, because it is too painful or embarassing, then you don’t need to.

This goes for any memory which you dealing with to start with the initial “tapping in” process, or any subsequent secondary memories which come up during the process. You can remain as specific or vague as you like when verbalizing these memories.

The main goal in processing in EMDR is to stay mindful and aware of what is coming up for you internally, both in terms of feelings and memories.

You don’t need to talk about what is coming up if you don’t want to; you just need to stay present with it and follow the movement of the therapist’s hand, or some other back and forward stimulus.

This can make EMDR a very useful form of psychotherapy for clients who have memories with a lot of guilt, shame and embarassment attached to them.

In standard talk therapy, they would be expected to talk through these memories in great detail; in EMDR, they don’t need to. They just need to stay with the memory internally, follow the outer stimulus and notice what else comes up.

This can make it a very effective therapy in bypassing these common barriers to progress in conventional therapy of not wanting to talk about uncomfortable memories, yet still getting clients in a much better place in terms of detaching from distressing memories and being less burdened by them.

Here are some examples of people who can benefit from the non verbal aspect of EMDR:

- People who have memories with a lot of shame, embarassment and humiliation attached to them.

- People who are distressed by memories of things which they have done, which they are ashamed or guilty about, but do not want to talk about in detail.

- In this regard, war veterans who have seen or done unpleasant things in their line of work that they don’t like discussing, but the memories of which continue to distress them, can benefit from the EMDR process.

- Clients who are traumatized to the extent they are very quiet and withdrawn, and are really not comfortable conversing much in any context, including therapy.

- People who are just naturally reserved and private, and not given to discussing their inner experience or life in great detail.

- People who have tried standard talk therapy and not had much success, and want a more direct way of addressing unpleasant past experiences.

Talking About Secondary Experiences With EMDR

However, despite what we have just said about not needing to discuss experiences if you don’t want to, it can be useful to mention things to your therapist which do come up during the process, if it is not too embarassing or distressing to do so.

The reason for this is that as the EMDR process unfolds, it can uncover secondary and repressed memories which had been long forgotten, in ways which can surprise the client. Things can come up from years ago that they had long surpressed.

The process of tapping into something, noticing your internal experience, doing the the eye movements, and then noticing what else comes up, can set of a chain reaction of secondary memories which are connected to the previous memory coming back into the client’s awareness.

The EMDR process can demonstrate how interesting and non linear the subconscious mind is, in that it can store memories in sometimes peculiar and bizarre patterns, such that memories are attached to each other in very unusual and seemingly illogical ways. However, there is always a connection there, however non-sensical it may seem at first.

If you possibly can, it can be useful to talk about this briefly with the therapist, even just to say what these secondary memories are in as much detail feels comfortable, simply because it may lead somewhere else useful.

See the video below from Dr James Alexander, where he gives a good example of how the EMDR process can uncover secondary memories which themselves lead onto other memories and so on. The eventual goal here is to reach an experience or negative feeling about oneself that is “core” or fundamental to the person, which once resolved, can deliver big improvements in self image and quality of life.

He emphasizes the fact that even if these connected memories feel silly or unconnected to the previous ones, it is better to mention them anyway if you can, because of where they may lead.

However, as we mentioned, no EMDR therapist will force you to talk about anything you don’t want to that comes up. Simply noticing is the primary goal with this process, and verbalizing is an optional extra that is entirely down to the client’s preference.

Discussing What Comes Up in EMDR

Getting Started With EMDR

For readers who are attracted to the non verbal aspect of EMDR therapy, and want to pursue it further, here are some resources to get started.

- See our Resources page for links to some popular books and websites on the topic.

- See also our Videos page for some good short and long form tutorials on how the EMDR process works, as well as some client testimonials on it’s effectiveness.

- See our full article on the EMDR process for much more detail on the 8 step framework of how it works.

- See our Find a Therapist page for links to resources in multiple countries to help find a qualified practitioner in your area.